Operating Room Etiquette for Students

5 Tips for Being in the O.R. for Newbies Being in an operating room for the first…

5 Tips for Being in the O.R. for Newbies

Being in an operating room for the first time can be a little overwhelming, especially if you have no idea what to expect. Scroll to the end for a brief explanation of a typical OR setup, or keep reading for my top tips for newcomers.

1. Always introduce yourself to the staff

I’ve never heard the team complain about a med student being clumsy or inept or incorrect… In fact, the ONLY time I ever heard the nurses and doctors complain about medical students was when they didn’t introduce themselves.

Upon overhearing that, I made it a point to introduce myself personally to the doctor and nurse. Sometimes that wasn’t possible, so I opted for a general greeting when I entered a room. Even a simple “good morning” works! But if I manage to make eye contact with the doctor(s) or nurse(s), I go over and shake their hand. I simply explain that I’m a fourth year medical student and state my name. One quick sentence and it’s done!

It’s awkward, it feels intrusive, but more often than not, it’s highly appreciated. [Once I didn’t get a chance to introduce myself to the scrub nurse because I couldn’t catch her eye and I could feel that she was annoyed at me… but ah well, what can you do except try your best?]

2. Maintain the sanctity of the sterile field

If you’re not quite sure what this means, definitely scroll down to the bottom to read about what an OR looks like.

For the rest of you, I don’t think I need to emphasize how important this is. My rule of thumb is to NOT make any sudden movements. Move cautiously, paying a lot of attention to your surroundings. If you’re not scrubbed in, keep a safe distance from the sterile field. This includes the scrub nurse, the little table(s), the surgeon and the patient, of course. Note that if you don’t, the scrub nurse will likely bark at you (and with good reason).

When you are scrubbed in, you have to be very very careful with what you touch. For instance, although you are scrubbed in and technically sterile, there are still parts of you that aren’t; namely your face, mask, hair net, etc. This means that you cannot fix your hair, adjust your mask, scratch an itch – none of it. It’s crazy how common touching our face is, and it takes only one tiny movement to disrupt the sterile field.

Some of these movements are so natural and habitual that we don’t even realize we’re doing them; it’s really really hard to resist these motions, and I’ve been very close to breaking sterility tons of times. So my tip is to be HYPERAWARE of your movements, and question each one. Try not to allow your body to go into automatic drive, and instead focus on your actions to the max. It’ll definitely come more naturally with time.

3. Ask questions (when appropriate)

Every hospital I’ve been to does things slightly differently; heck, every surgeon has their own personal preferences for how things ought to be done. As an example: scrubbing in. The official way is taught to us in med school, but I’ve also seen doctors scrubbing in in a dozen different ways.

So now, I tell the doctor: I’ve scrubbed in before, but each hospital seems to have different ways to do it, so if you see something I could be doing differently, could you please let me know? Sometimes they just nod and sometimes they explain their preferences, which gets a nice conversation going. The way I see it, I’ve warned them so I don’t have to worry about doing things wrong (quite as much).

Also, the more I worked with a surgeon (and the more I got to know him), the more comfortable I became with asking questions. Timing is key, of course. For instance, I would try to make it so my question wasn’t interfering with some critical step. I would also start to ask if I could palpate this or that, if he could explain that, etc. I am there to learn, after all, and a good surgeon should be more than happy to teach eager students!

This depends on your hospital, your surgeon and your relationship with him, of course. But in general, don’t be shy, but be vigilant so as not to interfere with his/her focus.

And when in doubt about something, ASK. Much better to ask than to mess something up!

4. Don’t take it personally

A surgery can be a high stress situation, and a lot of things need to go right for it to be successful. As such, there are moments of tension in some surgeries and the unpleasant reactions in these moments most often have absolutely NOTHING to do with us, the students.

So if you accidentally unsterilize yourself and the scrub nurse seems annoyed? Don’t beat yourself up. You can scrub back in and great, disaster averted!

If you accidentally hold something with too much force (or too little force) or at the wrong angle, and the surgeon roughly corrects your position? Don’t take it personally – s/he’s not angry at you, but most likely highly concentrated on the task at hand and maybe even a bit distracted.

If your hand slips and a retractor moves, it happens. [Although I would advise you to try to mention that the grip is slipping BEFORE any sudden movements are made, so as to avoid any adverse occurrences.]

In general, you’re there to learn, and you’re doing your best. Everyone has to start somewhere, and no one was a perfect OR assistant/surgeon without make a few mistakes. If they can’t understand that, that’s their problem, so do your best and don’t let some unpleasant people discourage you too much.

5. Prepare for your day in the OR the right way

This means three things:

A. Always make sure you’ve eaten. After I had my near-fainting spell while scrubbed in to assist with a digit repair, I vowed never to let my blood sugar drop. So on surgery days, I always make sure to have some sort of breakfast, and if I know I’m heading into a long surgery, I usually grab a snack too.

Surgeries can very intense – the hot lights and multiple layers may overheat you, the retraction/standing/stooping positions may tire you out, and the intense concentration can be exhausting. So give your body the fuel it needs!

B. Pee beforehand. Once an operation starts, you can’t exactly scrub out to pee (unless it’s an emergency, of course), so to avoid the unpleasantness of a full bladder, make sure you pee before heading in there!

C. Take your phone off loud or vibrate. Sometimes I’m told to keep my phone in my scrubs pocket, other times it’s placed on the computer table behind us. Either way, I would NOT want to be the cause of distraction should my phone unexpectedly go off. So I always check to make sure it’s set to silent (not vibrate) before heading in there.

I hope these tips helped remove some of the mystery around how to behave in an OR. If you have any more questions, please comment them below!

For a list of books I have read about surgery that I absolutely adored, check out my Med Reads Recommendation list here. And to get a glimpse of what studying in med school might look like, I have some YouTube videos up on my channel!

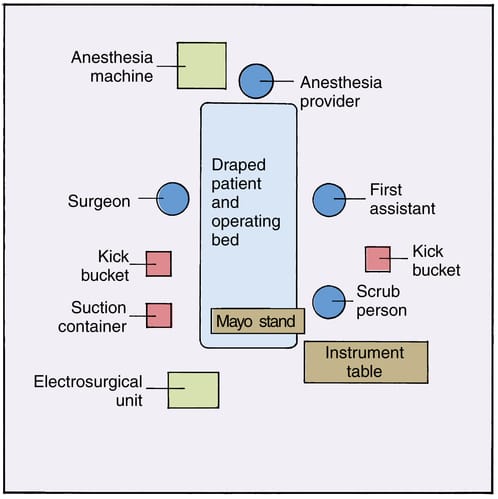

The Typical OR Set-up

OR setups tend to differ based on the hospital, the operation, the room; but there are a few things that are almost always present:

patient: usually the patient is ISOLATED via sterile drapes, so that only the part that is being operated on is exposed for the team. In most operations, the upper body/head of the patient is hidden by a partition that is also draped in sterile cloths, and behind that resides the anesthetic team.

anesthesia provider(s): they are NOT sterile; they sit behind the partition and make sure the patient is stable throughout the operation

surgeon and assistants (residents, medical students): they are STERILE, and should remain that way. Make sure you do not touch your head, face, or anything below the waist; those areas are all considered non-sterile.

scrub nurse: absolutely STERILE – s/he is the first to scrub in. S/he usually sets up all the equipment and usually helps the rest of the team get gloved and gowned. During the operation, the scrub nurse is the person who hands the surgeon/assistant team the appropriate tools. When needed, s/he can lend a helping (sterile) hand.

circulating nurse: this person is NOT sterile and is charged with handing anything that the surgical team may need to the scrub nurse in a sterile manner. They often also help by adjusting the lights, bringing in stools/the fluoroscope/whatever else is needed, and occasionally answering phones, wiping sweat, etc. Because they are not sterile, they are the sterile team’s link to the outside world.

Below is a diagram of a setup of a typical operating room; based on the description above, you should be able to test yourself and figure out which item needs to be sterile and which does not.