Volunteering in an ED as a medical student during the coronavirus pandemic

I’ve been volunteering at my university’s Emergency Department for the past two or so weeks, and since…

I’ve been volunteering at my university’s Emergency Department for the past two or so weeks, and since I talk about it a lot on my stories, I decided to make a blog post explaining what that really consists of. If you don’t follow me on Instagram, you can check it out here!

I just want to start off by saying – to me, it doesn’t feel like we, the medical students, are actually ‘essential’ and it’s far from ‘heroic’ – sometimes I wonder how useful we really are. But read on, and you’ll see what I mean!

As a bit of background: I’m a 5th year medical student in a 6th year program, so we’ve had a lot of theoretical classes but our clinical skills are definitely lacking. This is mostly because in our clinical classes, we get to observe a lot of everyday and extraordinary cases, but we don’t get to do much. From what I’ve seen, in the US 3rd and 4th year med students are given their own patients to ‘take care of,’ whereas our classes are usually in a group setting with the teacher/doctor demonstrating things and quizzing us before we move onto the next patient.

So keep that in mind as you continue.

How the ED has changed in the pandemic

The main change you can see in the emergency department (besides seeing surgical masks on everyone) is the concept of pre-triage. It takes place in a little shack that was erected in front of the building, and it’s an extra step to ensure healthcare worker (HCW) and patient safety.

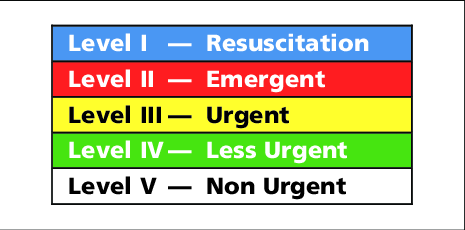

Triage in emergency medicine is an objective system used to determine who needs assistance first. Most countries have their own triage systems (ours is based on the Canadian one), but in general, they give each patient a score from 1 (most life-threatening) to 5 (non-life-threatening) based on the patient’s current symptoms. The idea is that this way, the patients who need it the most can get care first.

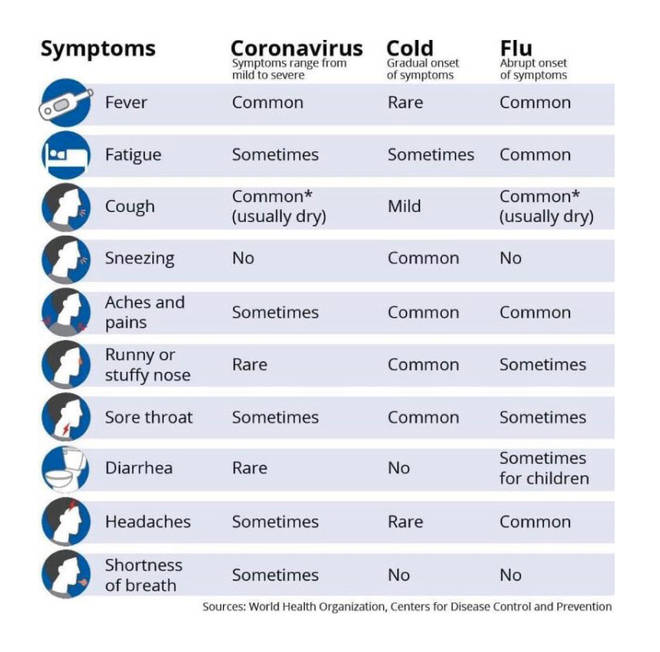

Pre-triage is thus a step BEFORE normal triage, in which we try to screen for people who could be potentially infectious. We take temperature, oxygen saturation and ask about a series of symptoms in an effort to figure out who could be infected with coronavirus.

Anyone who has any infectious symptoms (such as the ones listed on the right), we send to a section of the hospital that is colloquially referred to as the “Red Zone.” Here we have patients who may or may not be infected with coronavirus, and the staff who attend to those patients wear full personal protective equipment (PPE).

Normal triage: the rest of the patients, who have no infectious symptoms, get sent to normal triage, where they are questioned more specifically about their symptoms so that we can determine who needs help first.

>> Steps of triage: the patient has to be triaged within 10 minutes of arriving to the ED – this is important. During the triage process, we:

- identify the patient

- do a ‘quick look’: on first glance, how is the patient [Is he alive? on the cusp of death? normal? if the patient seems ok, we can continue]

- take the vital signs: heart rate, blood pressure, oxygen saturation, respiratory rate and temperature

- determine if there is pain (and the severity, from 0-10)

- ask about medication allergies

- take a brief past medical history (only the key facts)

This is meant to be a FAST initial survey of the patient’s imminent danger, and based on these facts that we’ve learned, we can give a more-or-less objective triage level that will tell the staff who to pay most attention to.

Side note

Headlines are filled to the brim with coronavirus this or that, but as our department head points out every day: people continue to get sick for non-coronavirus related reasons. It’s easy to forget that during this time of crisis, life and sickness continues. So we can’t have tunnel vision for coronavirus.

Despite that, the other thing that has changed in the ED is that patient influx has decreased – the ambulance corps has been instructed not to bring patients out of their homes unless they deem it truly necessary, and citizens have been encouraged by radio, TV and all kinds of social media campaigns to stay at home. As such, the number of patients we see is generally a bit lower than usual, although the uncertainty of the situation and the initiation of the Red Zone has resulted in an increased workload.

Medical students in the ED

So what is our role in all this? The HCWs work in 12 hour shifts, from 7am to 7pm, so we students have also adapted to those shifts. There are usually 6-8 medical students for each the day and the night shifts, and we’ve been assigned different tasks.

- TRIAGE: first and foremost, we’re in charge of doing the normal triage – we had a four hour ‘class’ on how to properly triage a patient, and with the assistance of a triage nurse or the attending, we are the ones who first see the incoming patients.

- PRE-TRIAGE: patients have a knack for arriving en masse, so 1-2 students usually help out at the pre-triage shack. The best is when two ambulances pull up simultaneously, while three patients arrive on foot, and chaos ensues. When this happens, we can truly be useful.

- NURSING: we help out as nurses’ aids – the funny thing is that the nurses are incredibly competent, so most of the time, it would take them three times as long to explain to us how to do something, than it would be for them to do it themselves. Even so, we try to help wherever we can, and the very helpful nurses actually try to ‘train’ us so we can be even more useful. This is really great, and anything we get to do makes for great practice for us. We:

- place IV lines and give infusions

- send blood/fluids to the labs

- this is especially important because it involves using the computer system, and since this pandemic started, a lot of non-ED doctors have been sent to the emergency department to help out. So there are pediatrician, gynecology, dermatology, radiology residents who all use different systems, and have no idea what’s usually done in the EM. I find that by knowing some of these key things, like sending labs for processing, we can help out the new doctors who are just learning on the job

- change bedding, diapers, escort patients to the bathroom

- place urinary catheters

- do bedside EKGs

- do A/VBGs and bedside INR

- monitor the patient’s parameters (hourly blood pressures, temperature, heart rate, O2 saturation)

- These tasks might not seem difficult (and for the nurse, they’re certainly not), but it requires a fair bit of know-how — from know where to find the IV lines or the diapers, to knowing how to turn the patient or how to properly remove a cannula — these are things they don’t teach in medical school, and although they’re simple, they’re still a ton of things we have yet to learn. So it’s awesome to get the chance to do that now.

- RED ZONE: willing students don full PPE and are taken into the Red Zone, where they do similar nursing/bedside tasks and essentially work as patient advocates.

- The HCWs are completely overwhelmed by long hours and too many shifts, and combined with the constant uncertainty of the situation, you can see they’re exhausted. There is undeniable tension, and I try to at least help the patients by being there, listening to their problems and offering words of comfort. I also try to check to see if their lab results have come back, or if their imaging studies are done, etc., and gently remind their doctors in cases where the patient has been waiting for a long time. This is a really sensitive task, and I try to be helpful without stepping on toes.

- DISINFECTION: we are also charged with regularly disinfecting all surfaces, door and cabinet handles, beds/wheelchairs, etc. OH, and we’ve got the lovely job of reminding patients and staff how to properly wear their masks (this definitely gets me more than a few annoyed looks).

- ODDS and ENDS: we also do some random, unquantifiable tasks – restocking cabinets, finding patient beds/wheelchairs, bringing patients (and staff hehe) food, cleaning out the staff fridge or doing the dishes in the staff kitchen, finding missing patients (they like to go a-wandering), delivering messages between Red Zone and the rest of the ED, run papers from one place to another — really, anything we can to try to take some of the pressure off the staff. The other day I was standing around and a doctor asked me if I had neurology already, and since I had, he asked me to do a quick neuro exam on a patient. Any abnormalities I would have found (which he had none), I would report to the doc.

On a regular day, there is always something to do – usually I do about 12-15,000 steps from running around, doing whatever I can to keep myself occupied. And if there are no patients (like yesterday, the first warm Sunday of the year), we sit outside in the sunshine and soak up some vitamin D with the staff. Despite the chaos and exhaustion, the mood is still lively and the staff spend a lot of time joking and venting, which is really nice to see and even be a part of.

Night shifts are much more relaxed. Usually patients arrive until about midnight, max until 2-3am, but then ZILCH. No one wants to venture outside when it’s cold and dark and they’re sleepy…which means we don’t have much to do, sadly. But it’s better for the patients this way, of course. As such, being on night shift doesn’t feel the most useful, but we try to augment our time by asking the docs or nurses to show us things.

For instance, last night two of my favorite doctors showed us medical students how to properly use the ultrasound. We’ve all learned about US in theory and practiced on each other once or twice, but now we had a more in-depth ‘class’ on how to do an eFAST US in the ER and how to position the transducer just so. This all went down at 4:45 am, mind you. So night shifts, while not always exciting, can be useful if we find ways to occupy ourselves.

The more time we spend here, the more the staff get to know us, and they get to ‘rely’ on us, which is great. Also, hopefully they’ll start to recognize what skills we possess and what we have yet to learn, and I’m hopeful that with time, we’ll be integrated into the department and become more and more helpful.

A few words on SAFETY

I think the #1 question I get asked is if I’m staying safe. In short, yes. I mean, I’m doing my best. I am lucky because we are provided with adequate PPE when interacting with suspected and confirmed COVID cases. The head of the department and the higher ups are placing enormous emphasis on the safety of the staff, and they recognize and reiterate that by not ensuring the safety of our healthcare workers, we are endangering the lives of all future patients.

The PPE we are given to wear is woefully uncomfortable. You have restricted range of motion, decreased peripheral vision; it’s hot and sweating and itchy. The masks are so tight that it leaves marks on your face, which hurt and scar, and breathing in the gear is undeniably difficult. Four hours in the full suit feels like a short lifetime, and it’s definitely taxing on the HCWs. That being said, I’m incredibly grateful that we have access to proper PPE, because I know that’s not the case in other parts of the world, and I’m so thankful that our institute works to ensure our safety.

In conclusion…

I was taught never to end an essay with ‘in conclusion,’ but despite the ardent begging of my high school literature teacher, here I am, ending my post with those dreadful word: in conclusion…

…this volunteering thing has its ups and downs. Since EM is the field I intend to go into, I mainly enjoy being here (people probably think I’m overeager). I’ve met so many medical students (since I’m in the English program, I don’t interact a lot with the native med students), which has been really great. I feel like I’ve been making friends with some like-minded 5th and 6th year students and I love it. Furthermore, some of the nursing and physician staff are also really nice to talk to and get to know, and I’ve gotten a ton of insight into the workings of a hospital emergency department by spending these weeks here.

The downs are that there is not always things for us to do, so there are a few hours of standing around (especially at night shift). Furthermore, not all of the staff is thrilled to have us there, so sometimes we’re met with frustration because we are constantly in the way. And finally, night shifts really throw off my internal rhythm (those of you who know me know that I have a routine and I stick to it), so doing these occasional night shifts kind of throws that off.

Also, there’s a lot we know (textbook knowledge, really) and a lot we have yet to learn. There are so many clinical things that we could practice while there, but sadly that would require additional energy on the part of the physicians. So for now, I’m not really pushing the residents or attendings to teach me/us, and instead trying to be helpful here and there.

And anyway, there’s other things to learn too — hands-on skills that they don’t even teach in medical school. And some basic life-skills, like: the other day, one of my favorite docs asked us to quickly bring two patients to a different hallway to wait for their transport, so we did. Next time we saw her, she asked if the transport ever arrived, and we said… we don’t know, we just left them there. Her jaw dropped, and she told us that she’d meant for us to stay with the patient until the transport came. Whoops. We laughed, and went back to check on the patients (they were ok), and now: lesson learned. Do not abandon patients in random hallways, pandemic or not. [insert facepalm here] Truly not stuff you learn in textbooks.

So all in all, I’m happy to get to spend some of my quarantine being back in the hospitals.

I do have to say, I don’t feel like we’re all that essential – the reason I use the word essential is because the chief of the ED often tells us that the department would have collapsed without the volunteers. I have trouble believing that, but it’s still nice to hear.

The staff is so competent that it’s no doubt that they would get by without us. Our presence can be helpful, but not necessarily ‘essential.’ But perhaps every shelf that they don’t have to restock is a bit more time they get to take a breather and get a coffee or sit down and rest their legs.

The takeaway

I’ve met two kinds of doctors: the kind that is able to do a lot of the bedside and nursing procedures, and the ones that aren’t. A few of the younger doctors shy away from venipuncture or hanging IV lines because they’ve never done it before and aren’t sure how to, which is usually not an issue because there is always a skilled nurse in the vicinity. But in a time of crisis such as this, when the nursing shortage is palpable, they have no one to turn to. In swoop the other kind of doctor: those that are perfectly capable of taking an arterial blood gas or administering meds.

I’d like to be this second type of doctor, and so the little practical hands-on skills I’m learning here during my 12 hour shifts will be very beneficial when I graduate from medical school in about a year.

As for the patients, we try to do our best to provide psychological help and emotional support – I know they appreciate it because they say thank you a lot, and that means a lot to me, too. The other day, an elderly lady with moderate dementia hugged me and although it was touching, it wasn’t exactly the most appropriate in terms of infection control.

Needless to say, things during this pandemic are uncertain; protocols aren’t yet in place and ideas of what’s the ‘best way’ to treat COVID patients is changing constantly. With the situation developing daily, it’s hard to keep up, and a lot of chaos has ensued. It’s a privilege to play a small part in this unfolding crisis.

Please stay home, stay safe, and stay sane. If you have any questions, comment below.

Cover photo by Anna Shvets from Pexels