Why You Should Do Research in Medical School

And How to Go About Pursuing It I get a ton of questions about how to do…

And How to Go About Pursuing It

I get a ton of questions about how to do research in medical school, so here are a few steps you could take to land yourself a research position. I’m still in the early phases of my own foray into the world of research, so these are truly the words of a newbie. But perhaps this newbie can give a few tips on how to start your own journey!

But first, if you’ve ever thought about doing research but you’re not sure if you should even bother, here are 5 EXCELLENT reasons why delving into the world of research would be a smart thing to do.

- You get to be on the front lines of science, progressing our knowledge, or at least attempting to.

- You get to expand your skill set and practice critical thinking.

- You get to meet passionate, like-minded people and it’s really inspirational.

- You get to start building your professional portfolio; most institutions will look favorably on x amount of years of research involvement.*

- You get to travel to conferences and see the world, all for a scientific cause.

This is by no means a comprehensive list; there are lots of great things about research, but I just wanted to list a few and get the cogs spinning.

I think research is an incredible field. Although I don’t want to dedicate my life to solely research when I’m done with medical school (as in, I’d like to be a clinician), I think it’s really important (and exciting) work. I once heard it said that doctors just muck about, treating patients and waiting until the researchers figure out the actual cure. It’s definitely not as simple as that, but there’s so much that research has given us.

In EM, which is my intended field, research plays a special role: clinical research allows doctors to see if the current protocols work well and save lives, and if things are going awry, they use the scientific method to figure out where/why/how and to bring global changes to policy. This type of research really excites me – with a one-on-one patient interaction, we change a life. But by implementing a new life-saving protocol, we can change many.

*Please note: I’m not recommending doing research JUST for your resume/CV; lack of passion about a topic/cause will make it difficult to put your energy into it and it will show.

How to Find a Research Opportunity

This really depends on the institution you’re studying at, so take that into consideration. But here are the steps you can take (and that I took) to land myself a research “position”. The key is to be proactive, because honestly, no one will do it for you. Search and hunt and email until you’re where you want to be.

Be appropriately aggressive.

– my mentor

Start by thinking about what kind of research you’d be interested in. Here are some things to consider, and if you don’t know what these words mean, scroll down to the bottom for a quick list of definitions for things with * next to it):

- which department/institute/subject do you want to do research in? (anatomy, pathology, microbiology, physiology, cardiology? as many departments as your university has, that’s how many research groups there will be, so think about what class interested you a lot or which you’d like to learn more about)

- clinical or laboratory research?*

- if laboratory research, are you interested in a wet or dry lab?*

- what kind of tasks do you want to have: do you want to work on a computer? do you want to do biostats and/or data analysis? do you want to work with animals and/or cells, specimens, cadavers?

These are just some of the things you should consider, so you have an idea of what you’d like to do. For example, even before ever setting foot in a research lab, I knew I didn’t want to spend my hours on a computer, doing data analysis. So that helped narrow it down a lot.

First, check if your medical school has a program in place to match students with research opportunities. There might be an office that deals with that, and if that’s well organized, check their website, find an FAQ or even shoot the contact person an email. Their job is to help you, so don’t be shy.

If your medical school doesn’t have such a research system in place, that doesn’t mean that you’re not going to be able to find research. You just have to be a bit more independent.

How to get the ball rolling

There are two ways you could approach the situation now; the second is my preferred way, but the first is just as good. Both methods require a bit of luck.

- Via “cold” emailing: this means that you find someone’s email address online and send them an email out of the blue, stating your desire to join their research project, and you hope for the best. Doing a bit of research about their topics helps make your interest seem genuine (which we hope it is!), and you can discuss specifically what attracts you to the project in question.

- Via a contact: you can ask a friend or a professor who already knows and likes you in that department/field, and mention your interest to them. They’ll likely be eager to help you find a willing mentor or recommend a good way to go about it. Another excellent way is to go up to the lecturer after an interesting presentation, and ask questions, perhaps even mention your interest. They’ll likely give you an email address through which you can contact them.

All of this should be prefaced with RESEARCH. You should do some browsing on the internet, but specifically, on your university departments’ homepage. Most departments will have something that looks like this:

Some important things:

- Don’t get discouraged if no one answers your emails. It happens. These people are incredibly busy, and things fall through. Keep looking, and don’t stop til you’ve found someone who will take you in.

- It’s not necessarily the topic that makes a good research project, but rather, the advisor; I’ve heard it said that you should choose your research op based on the latter rather than the former.

- Know how many hours a week you’re able/willing to dedicate to a project, and make sure you and your advisor are on the same page your expectations.

- Many professors and doctors love to meet young people who share their passions and have aspirations; show you’re interested, and that you’re willing to put in the work, and you’ll get the results you wanted.

This is perhaps the most important piece of advice: Do not stop until you’ve found someone to take you under his or her wings. We make our own futures – don’t wait around until things fall into your lap. Be a go-getter and write your own book.

Some Research Tools to get you Started

You’ve gotten a research topic or joined a project, and now have no idea how to proceed? Join the club.

I genuinely have no idea what I’m doing. So I started with doing what I do best – Googling. I searched a TON of websites and talked to some people who gave me pointers. I still don’t know what I’m doing, but at least I’m doing it in a more organized way now.

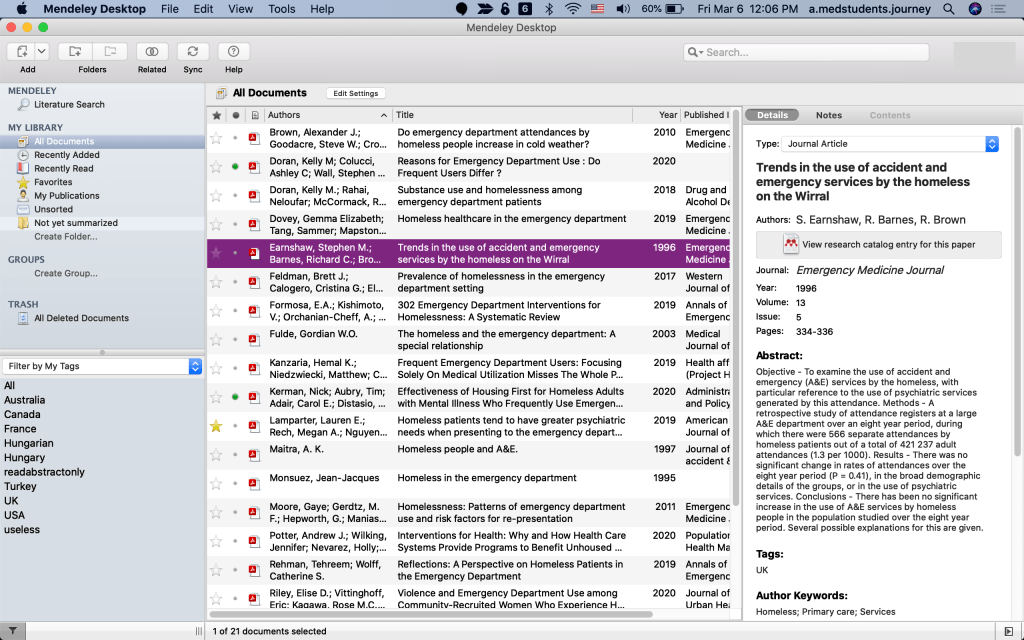

Aggregate your research papers with Mendeley

Incredible program that’s FREE and allows you to keep track and easily cite all your papers. My first task for my research project was to find out what else is out there regarding our topic, so I searched a bunch of websites to find as many articles as I could reasonably look through and downloaded them to Mendeley.

There are two alternative programs that are highly recommended (EndNote and Zotero). I’ve tried both but I liked Mendeley the best because it has its own internal PDF reader and a few other subtle things. Here’s a screenshot from my own view of Mendeley:

Access scientific journals with Sci-Hub

A good friend of mine showed me this website, linked here. Even though our university helps us access scientific journals through the uni network, we’re not always doing our work on campus. So with this website, I can work from anywhere.

Scour the Internet for related articles

I didn’t know where to start, but I just dived right. I Googled which are the best journals for my field (emergency medicine), and went directly to different variations of “X Journal of EM.” I also used PubMed to find articles, as well as ResearchGate.

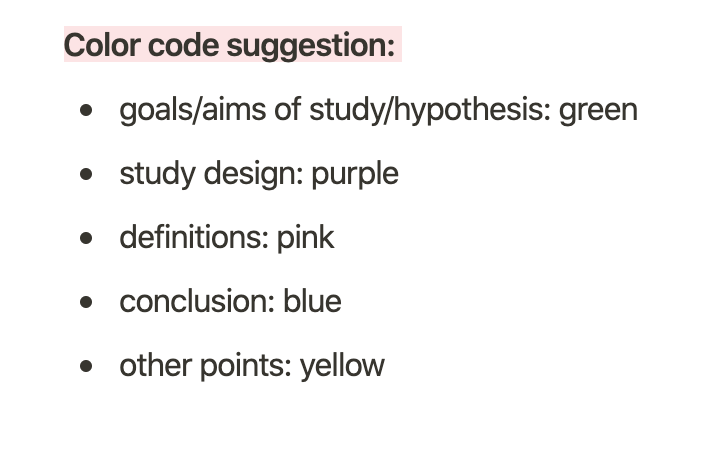

Reading articles & summarizing them

(Again) I had no idea where to start… so I started reading the first article. Lucky for me, my topic isn’t that technically difficult, but I decided after I finished my first few articles that I was seriously lacking any sort of structure to my reading. So I came up with this color code to help me organize my highlighting, and although it’s pretty general, it helped me read the articles more critically.

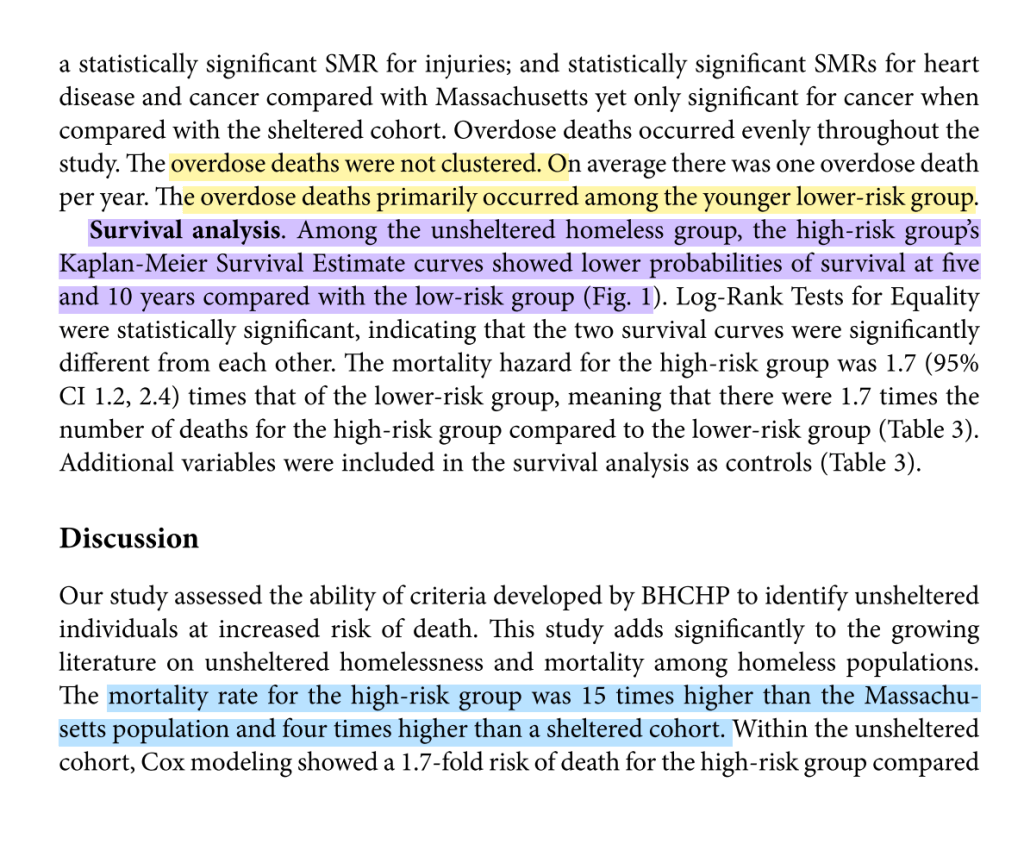

Here’s a snapshot from an article I read through: I used the color code to highlight the key things for myself that I wanted to include in my summary.

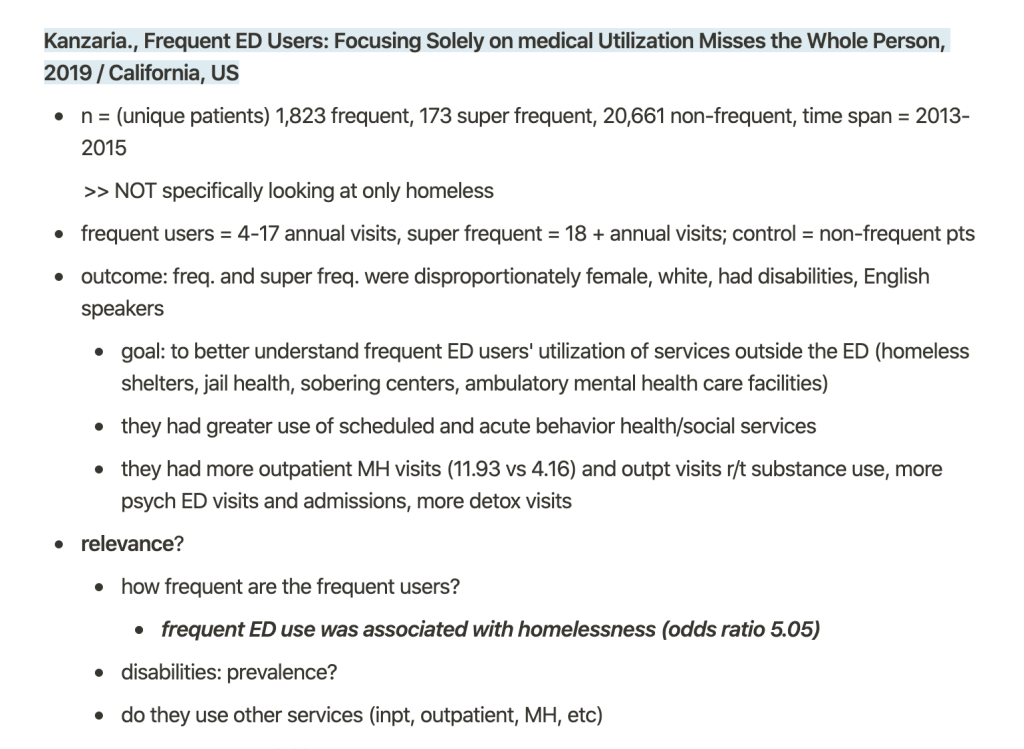

In my summary, I just wrote generic information (title, country of origin, date, sample size), and then listed the relevance/questions that arose while reading through this. It’s sort of a critical analysis that helped me answer the question, “what can we use from this journal article?”

I decided to use Notion because it’s a simple but well-organized FREE program. It’s nice, minimalistic and easy to use. Click here to use my invite link and try it out – it’s completely free, and useful for making to do lists, taking notes, etc.

As much as I like Notion, for my thesis writing I might switch to Google Docs (also free, easier to format things and allow for collaboration), but I haven’t made the switch yet. Here’s a snapshot of one of my summaries in Notion:

And finally, we’ll be using Excel to collect our data – might try out some other programs (like LaTex), but more on that if I decide to pursue them!

Thank you for reading!

I hope this was helpful. Good luck with your work!

Special thanks to a good friend for helping with this article. Credits for reasons to do research go to him!